FLBS Researcher Nanette Nelson Takes on Aquatic Invasive Species with the Tools of Economics

by Heather Fraley, Environmental Science and Natural Resource Journalism Intern

Flathead Lake is a boating and fishing paradise, a cultural touchstone and a summer home mecca. It’s easy to talk about the good things the lake provides for people, but it’s complicated to represent those benefits in dollar values. That’s Nanette Nelson’s job.

FLBS Research Economist Nanette Nelson.

Nelson is an environmental economist. She helps policy makers understand what natural resources provide in monetary value. For example, she helps answer the question what is Flathead Lake’s clean water worth? She works at the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake Biological Station, where she’s been for a year and a half. She spent much of her career at the University of Wyoming.

The benefits that ecosystems provide for people are known as ecosystem services. These services include water for irrigation, wildlife habitat, recreation and fishing. Without researchers like Nelson, ecosystem services aren’t included in most economic analyses or policy decisions.

“A smarter person than me said ‘economics is the currency of modern policy,’” says Nelson. “Right now, that is just how we make decisions. It’s in dollars…so if someone like me doesn’t put a dollar value on ecosystem services, it goes in as zero. People don’t consider it.”

Nelson uses scientifically rigorous economic research methods to give voice to how valuable these services are to people surrounding Flathead Lake.

What is Flathead Lake Worth?

Last year, Nelson researched and produced a report showing the importance of outdoor recreation in the Flathead Valley economy. She reported that nonresidents spent $598 million in 2015 in Flathead County alone. This spending is driven by beautiful outdoor recreation areas like Flathead Lake.

Nelson stresses that there is no way to put a price on Flathead Lake as a whole. Instead, ecosystem service values are calculated around change. If there is a policy change that will affect water quality or some other service, an economic valuation can be done. Trying to give value to the presence or absence of an entire resource just isn’t realistic.

“Because we are interested in how happy people are around Flathead Lake, we can measure changes in benefits, but not the absolute value of the lake.” said Nelson.

In 2018, FLBS Research Economist Nanette Nelson met with Energy Keepers CEO Brian Lipscomb to discuss the potential mitigation costs and lost revenue if invasive mussels were to reach the hydroelectric plant on the Flathead River.

How Much Would Invasive Mussels Cost the State?

One big potential change to Flathead Lake is the threat of aquatic invasive species (AIS), specifically zebra and quagga mussels.

These mussels are originally from the Black and Caspian seas of Eurasia, but traveled to the Great Lakes region in ships’ ballast water in the 1980s. They have been marching their way westward, and were found in Tiber Reservoir in Central Montana in 2016. So far there are no invasive mussels in the Columbia River Basin, which includes the Flathead, Kootenai and Clark Fork Watersheds in Montana.

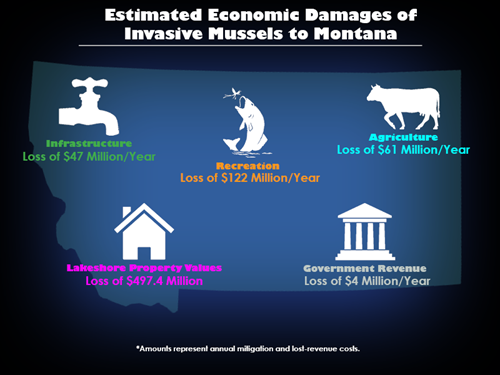

In her report, Nelson calculated that the arrival of invasive mussels could potentially cost Montana more than $230 million per year in mitigation costs and lost revenue. Recreation, which plays a crucial role in local economies in Montana, especially in the Flathead, could see a loss of $122 million per year. Government revenue, especially local government, could see an estimated loss of $4 million per year.

Nelson determined that agriculture statewide could pay up to $60 million per year in mitigation costs. Hydropower could see increased operating costs, and Energy Keepers, the new owners of the Se̓liš Ksanka Ql̓ispe̓ Dam, formerly known as Kerr Dam, could face a loss of $8 million per year if invasive mussels establish. This would directly impact the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

Lakeshore property values in Montana, however, could feel the biggest loss. When mussels establish, they completely change a lake’s ecology. In North American waters, the mussels rapidly multiply and take over. Because they eat the majority of the food available to other organisms, invasive mussels drastically alter the ecosystem and by extension human recreation and enjoyment. In Montana, an invasive mussel infestation could mean a loss to lakeshore property values estimated at nearly $500 million.

This chart shows a few of the potential mitigation costs and revenue losses to Montana industries, should invasive mussels ever infest Montana waters.

More about Nanette’s economic study on invasive mussels can be found at the FLBS website.

Putting the Research into Action

Nelson is driven to share her reports with policy-makers and the public. She presented her research at the state legislative session in January, which was good timing. The current level of Montana’s aquatic invasive species funding is approximately $6.5 million per year, roughly 3 percent of the estimated $234 million annual mitigation and lost-revenue costs cited in Nelson’s report. Further funding for preventing aquatic invasive species has been a big topic during the 2019 legislative session.

She also presented the findings at the Associated Chambers of Commerce of the Flathead Valley meeting in February 2019. Those who didn’t have the chance to hear her presentation at the Associated Chambers meeting in person may have read about it. The Associated Chamber is politically active, and has a membership that includes over 700 businesses and 4,000 total representatives, most of whom are owners and managers of businesses in the Flathead Valley.

“This is an important topic. It’s listed as one of our top issues for this year,” says Joe Unterreiner, president of the Kalispell Chamber of Commerce.

But Nelson doesn’t just direct her outreach toward government and business organizations. She works to share her findings with the general public as well.

She gave a talk explaining her environmental economics work to a packed room at a “Science on Tap Flathead” event in Woods Bay, Montana in the fall of 2018. Presently, she is connecting with communities around the lake in an effort to open dialogues and increase understanding about the potential economic damages described in her invasive mussel report.

What are People Willing to Pay to Stop Invasive Mussels?

Using survey methods, Nelson can ask people questions, and find out how much money the average person is willing to pay to keep a benefit that they get from the environment.

She is in the beginning stages of an exciting new collaboration with Shandin Pete, a hydrology professor from Salish and Kootenai College. Pete is a tribal member with extensive scientific experience. Pete is Salish, whose original tribal homeland is in the Bitterroot Mountains, but he grew up around the lake, and he knows the nuances of the place.

One of the main hurdles Nelson faces in creating the surveys is figuring out valuation across cultures.

People with different cultural backgrounds can view ecological benefits differently, and being sensitive to these differences is important. More than half of Flathead Lake is on the Flathead Indian Reservation, and managed by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

Nelson and Pete are funded by a US Department of Agriculture grant. They will produce a survey that will elicit the preferences of tribal members around the lake about invasive mussels.

Pete says including multiple backgrounds of people is important to value the lake.

“There’s no way you can make assumptions about a place until you learn about the people and their opinions, and not just one group of people, all users,” he said. “That’s just good science, and a good way to move forward.”