Zebra Mussels

Problem

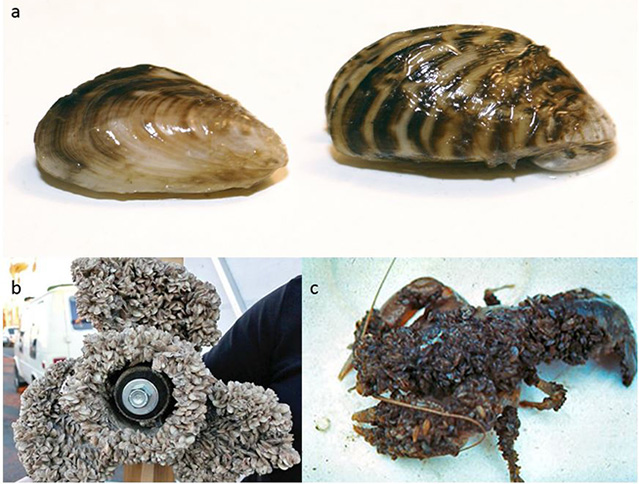

Zebra and quagga mussels (Dreissena polymorpha and D. rostriformis) are two of the world’s most problematic biological invaders (Figure 1a). They are colonizing and devastating lakes and rivers across North America. They recently invaded Montana and might soon invade the Columbia River drainage. The Independent Economic Analysis Board has calculated the economic risk of a mussel invasion in the Columbia River drainage to cost the region tens of millions of dollars annually (IEAB 2013). Moreover, it would threaten the health of native fish populations, in which billions of dollars have already been invested (IEAB 2013). These invasive mussels can clog water intakes and damage equipment by attaching to boat motors and hard surfaces. They can collapse fisheries, smother native species including mussels and crayfish (Figure 1 b,c), and litter beaches with their sharp shells that cut the feet of children and pets. Adult zebra mussels can survive out of water for days, attached to boat hulls or fishing equipment and thus can be spread easily and widely among lakes and regions (Minnesota DNR). Larval mussels can survive for days in water left in boat bilges or motors or equipment.

Figure 1. (a) Comparison of quagga (left) and zebra (right) mussels (Michigan Sea Grant). (b) Boat propeller encrusted with Dreissenid mussels (Protect Our Freshwater) (c) Crayfish covered in mussels leading to a slow death (SLELO PRISM).

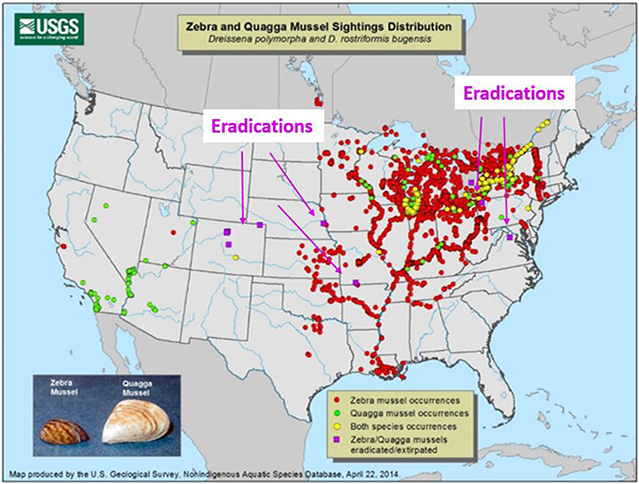

Figure 2. Locations of zebra and quagga mussel occurrences (red and green, respectively), and occurrences of both species (yellow). The arrows and nine purple squares are some of locations where eradication was successful (USGS 2014).

Zebra/Quagga Mussels Threat Video

Solutions: eDNA Tests to help Prevent Zebra Mussel Invasion

Our DNA-based PCR tests provide sensitive and rapid identification from water samples; this is crucial for the early detection and containment to help prevent their spread. Success of control strategies (e.g., quarantine, removal, or decontamination of boats and docks; or killing mussels with chemicals) is improved by early detection (Hosler 2011; Sepulveda et al. 2012) and eradication is more likely possible if invaders are discovered before the population becomes well established (Figure 2).

Early detection is increasingly feasible thanks to recent advances in genetic technologies using environmental DNA (eDNA). Water samples contain eDNA that can be extracted from the sample and used for the detection of tiny organisms (larvae) or cells sloughed from a target species via PCR testing (Beja-Pereira et al. 2009; Blanchet 2012). Surprisingly, relatively little research has been published on the sensitivity and reliability of genetic methods for detection of Dreissenid mussels (but see Gingera et al. 2016). We have developed and are refining field sampling protocols and DNA tests for the early-detection of Dreissena taxa from plankton tow samples from multiple lakes and streams in Montana and the Pacific North West.

Development of field eDNA sampling protocols

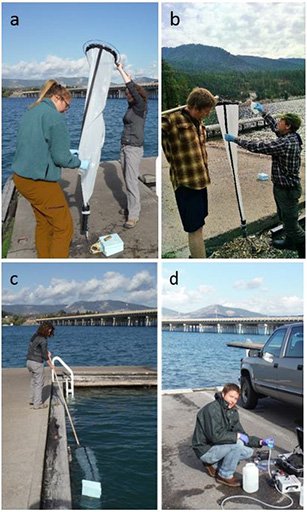

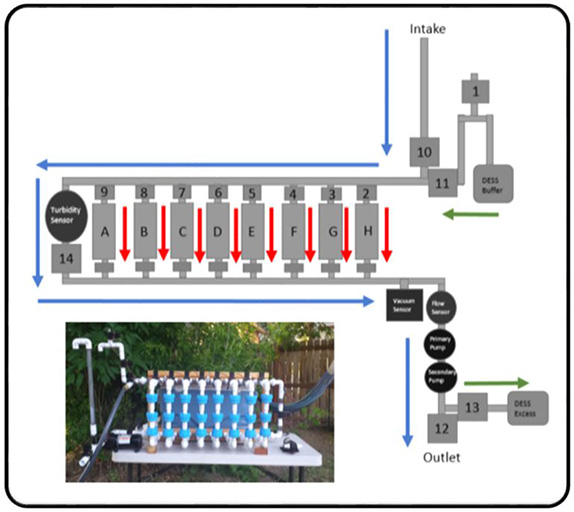

We have developed and validated a large volume water sampling protocol for lakes and streams (Figure 3) (Shabacker et al. in prep). We also have new equipment for collecting eDNA from large volumes of water autonomously, i.e. automatically (and repeatedly) without a human present (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Large volume water sample for environmental DNA (eDNA) collection by plankton tow net (a,b,c) versus traditional sampling (d).

Figure 4. Schematic and photo of autonomous sampler. Blue Arrows: Primary flow path for water through the instrument. Green arrows: Flow path for eDNA sample preservative. Red Arrows: Sample flow paths.

References

- Beja-Pereira, A., Oliveira R., Schwartz M.K., Luikart G. (2009) Advancing ecological understanding through technological transformation in noninvasive genetics. Mol Ecol Res 9, 1279–1301.

- Blanchet S (2012) The use of molecular tools in invasion biology: an emphasis on freshwater ecosystems. Fish Management Ecology 19: 120–132.

- Gingera et al. (2016) Environmental DNA as a detection tool for zebra mussels Dreissena polymorpha (Pallas, 1771) at the forefront of an invasion event in Lake Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Management of Biological Invasions 8: 287-300. https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2017.8.3.03

- Hosler DM (2011) Early detection of dreissenid species—zebra/quagga mussels in water systems. Aquatic Invasions 6: 217–222.

- Independent Economic Analysis Board (IEAB). (2013). Invasive mussels update, economic risk associated with the potential establishment of zebra and quagga mussels in the Columbia River Basin. Task Number 201. Document IEAB 2013–2.

- Schabacker J., S.J. Amish, A. Sepulveda, B. Gardner, D. Miller, Y. Wang, G. Luikart. Improved eDNA detection using large volume water samples and seasonal sampling. In Prep.

- Sepulveda A, Ray A, Al-Chokhachy R, Muhlfeld C, Gresswell R, Gross J, Kershner J (2012) Aquatic invasive species: lessons from Cancer Research The medical community’s successes in fighting cancer offer a model for preventing the spread of harmful invasive species. American Scientist 100:234–242.

- Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, “Zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha).” Aquatic Invasive Species, www.dnr.state.mn.us/invasives/aquaticanimals/zebramussel/index.html.

Eurasian Watermilfoil

Problem

Eurasian milfoil is an aquatic invader introduced to North America in the 1940s that has the power to dominate bays to the extent that it is almost impossible to swim, fish, or a drive a boat through entire waterbodies (Figure 1, Figure 2). Swimmers have drowned due to the thick dense matting of EWM (Kootenai County Noxious Weed Control). In the United States, millions of dollars have been spent on individual lakes trying to contain EWM blooms in order to maintain access to boat launches and docks. Some property values have decreased up to 13% due to this aquatic invader’s presence (Horsch and Lewis 2008) and millions of dollars have been spent at national level in effort to control EWM populations (USGS).

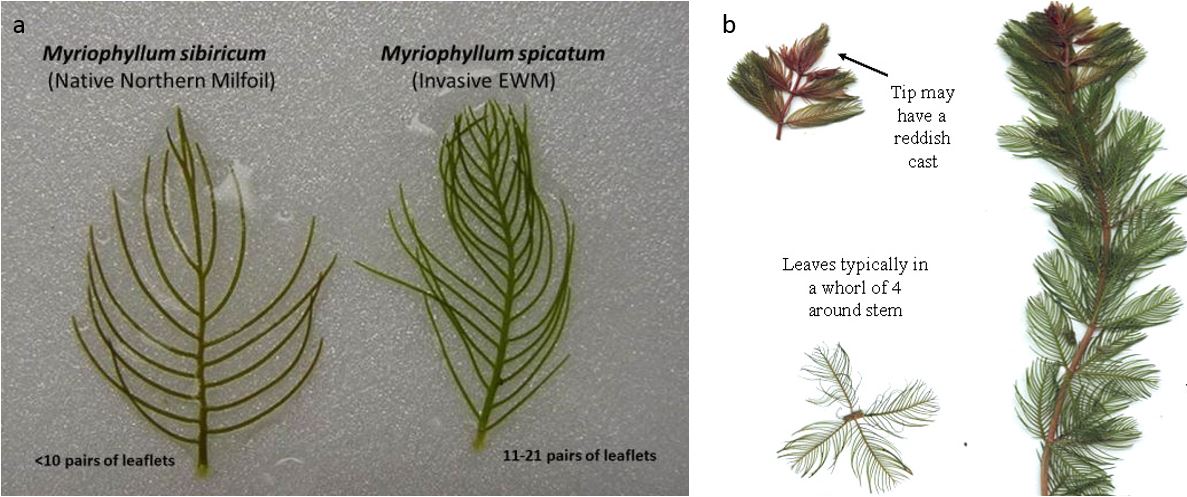

Figure 1. (a) Comparison of the native northern milfoil (left) to the invasive Eurasian milfoil (right) (USGS). (b) Eurasian milfoil individual plant and cross section of its leaves (Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation).

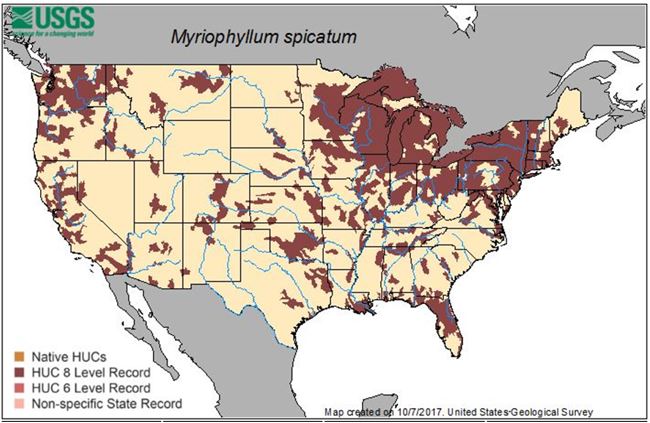

Figure 2. Geographic distribution of Eurasian milfoil in the United States 2017 (USGS).

Ecologically, the presence of EWM has a devastating toll. It grows and spreads rapidly across the surface of a lake, reducing the amount of light reaching into the waterbody and killing off native species (Smith and Barko 1990) (Figure 3). When EWM is present in large abundance over other native plant species, the aquatic invertebrates and organisms that rely on native plants as a source of food and shelter disappear. The dense masses of EWM eventually decay in the waterbodies they inhabit causing degraded water quality and anoxic water conditions that are harmful for fish populations (USGS). Once EWM becomes established, it is extremely difficult to eliminate from a waterbody; thus, early detection and rapid response is critical to preventing the spread of this aquatic invader (Sea Grant Michigan).

Figure 3.Dense matting of Eurasian milfoil lake infestation (Sea Grant Michigan).

Solution

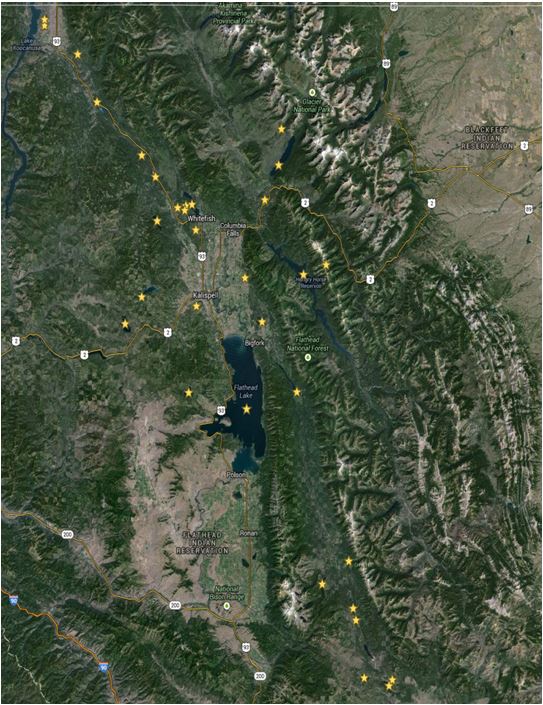

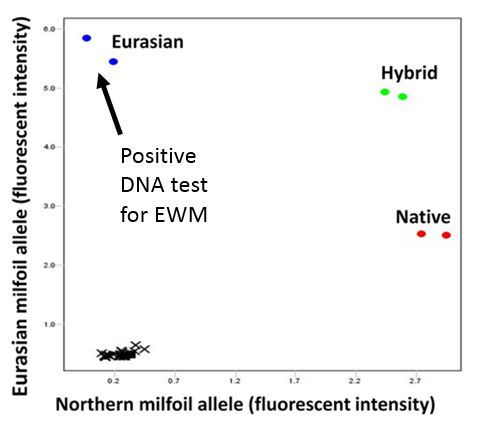

We are in collaboration with several agencies to test large volume eDNA samples across many high-traffic waterbodies in Western Montana including Swan, Holland, Van, Lindbergh, Whitefish, Blanchard, and Beaver Lakes (Figure 3). eDNA testing for Eurasian milfoil is crucial for early detection and eradication. We have a species-specific PCR assay that detects Eurasian milfoil. We also use a second PCR assay that detects native northern watermilfoil and acts as a positive control (Figure 4). Detection of the native watermilfoil indicates that effective sampling, preservation, and PCR amplification occurred, suggesting that the invasive species would have likely been detected had it been present.

Figure 4. Sampling locations of Eurasian milfoil in Flathead Lake and surrounding lakes in Montana. At some locations multiple samples are taken annually in both summer and fall (e.g. 10 locations in Flathead Lake) when enough funding exists for the testing.

Figure 5. Real-time PCR amplification plot showing fluorescent signal from Eurasian (blue), native (red), and hybrid (green) milfoil DNA. Negative controls (black), which contain no milfoil DNA, cluster near the graph’s origin.

References

- Horsch, E.J., Lewis, D.J., 2009. The effects of aquatic invasive species on property values: evidence from a quasi experiment. Land Econ. 85, 391–409.

- Kootenai County Noxious Weed Control, “Eurasian Watermilfoil.” Kootenai County, Idaho, www.kcweeds.com

- Smith, C. S. and J. W. Barko. 1990. Ecology of Eurasian watermilfoil. Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 28:55–64.

- United States Geological Survey, “Eurasian Watermilfoil—species profile.” Nonindigenous Aquatic Species, www.nas.er.usgs.gov

eDNA Protocols

Tow Protocol:

Page Under Construction

eDNA Glossary

eDNA Glossary

Page Under Construction