How Clean is Flathead Lake Really? Visiting Researcher looks for Plastic Pollution in Flathead Lake

by Heather Fraley, Environmental Science and Natural Resource Journalism Intern

Lake researcher Xiong Xiong peers into a clear glass jar filled with water, plant matter, and a thin, 3-inch-long piece of plastic. It looks like a bristle from a broom or maybe a piece of fishing line.

Flathead Lake is well-known for its brilliantly clear, cold water, but unseen pollutants could be lurking in the seemingly pristine surface water.

Chinese postdoctoral researcher Xiong Xiong is spending a year at the Flathead Lake Biological Station working with director Jim Elser. He’s trying to find out if tiny pieces of plastic known as microplastics are polluting the waters of Flathead Lake, and if so, how concentrated they are. “It looks quite clean, but if this clean lake is suffering from plastics I want to check that,” Xiong says.

Researcher Xiong Xiong takes the first water samples looking for microplastics in Flathead Lake. In one of his twelve samples he found a large piece of plastic several inches long. Photo Heather Fraley

Pieces of plastic smaller than five millimeters in size are known as microplastics. Microplastics include a wide variety of shapes from fragments to fibers. One of these types, microfibers, are everywhere. They can even be found in your polyester t-shirt or fleece coat. Microfibers can be carried into the water system after a normal load of laundry.

Plastic does not easily biodegrade. Natural processes break it into smaller and smaller pieces over the years without actually changing its structure. Decades’ worth of broken-down plastic can still be found floating around like suds in a bath tub years after it went into the water.

In his first water sample from Flathead Lake, Xiong found a thin piece of plastic. Although not microplastic because it’s greater than 5mm, bigger plastics could be a problem too, because they eventually break down to microplastic.

Microplastic is a huge pollution problem in water bodies around the world, and it’s becoming especially well-known in the oceans, where large piles of garbage accumulate. The largest ocean garbage patch is four times the size of the entire state of Montana in surface area. A lot of it is plastic that’s slowly breaking down.

Most microplastics research has been done on the ocean. “I think people think it’s more serious in the ocean, but we want to find the situation in the freshwater inland because many people live inland, and we need the freshwater,” says Xiong. “It may affect our daily life more directly than the plastic in the ocean.”

Xiong’s most recent work, including the work he did for his PhD at the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Wuhan, China, was testing highland freshwater lakes in the Tibetan Plateau for the presence of microplastics. There are a lot less people on the Tibetan plateau than there are in the big cities of China, but Xiong found that the lakes still contain microplastics at concentrations high enough to cause concern. He wants to see if a lake in the sparsely populated Flathead Valley, Montana might be carrying the same kind of baggage.

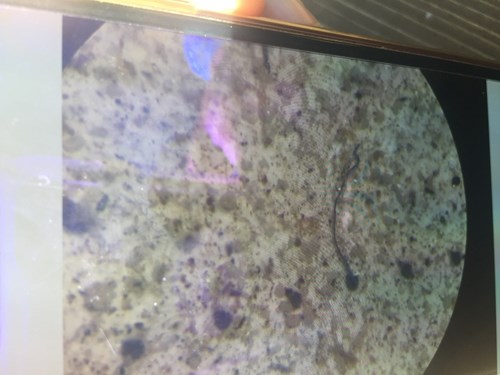

A suspicious fiber found in a deposition sample from Flathead Lake. Researcher Xiong Xiong hasn’t found any confirmed microplastics, but he will soon start testing his lake water samples to see if plastic is present. Photo courtesy Xiong Xiong.

Microplastics are thought to absorb toxins, and the toxins can move up through the food chain and end up in fish. Even now, there are guidelines about how much and what size fish you should eat out of Flathead Lake due to accumulated mercury. The suggested serving-size cards that state and tribal wildlife agencies pass out to anglers don’t factor in potential toxins from plastic. If there are microplastics in the lake, these toxins need to be evaluated.

Not only could microplastics potentially get into our wild-caught food, there’s also been some recent evidence that plastic particles are making it into commercial, bottled drinking water. Scientists from the State University of New York at Fredonia were commissioned by journalists to test for microplastics in bottled water, and found it in almost all of the water they tested. The report was released in 2018. The study has yet to be peer-reviewed, but it’s still indicative of a big problem.

Microplastics have already been found close to home in the Gallatin River in Southwest Montana by Adventure Scientists, a non-profit organization based in Bozeman, Montana. Citizen scientists collected water samples from 70 sites in the Gallatin Watershed, revealing plastic pollution.

For his own tests for the presence of microplastic in Flathead Lake, Xiong has gathered water samples from twelve locations around the lake with his windsock-shaped sampling net. He tows the mesh net behind a boat, and it plucks up any particles in the water.

He has also been piggy-backing on the long-term data sampling that’s been going on every few weeks in Flathead Lake and its tributaries since the 1970’s, known as the Flathead Lake Monitoring Program, or FMP. The FMP crew intercepts samples of what falls out of the air before it is deposited in the lake. These are called deposition samples. Xiong has been checking some of these samples to see if there are microplastics in them. He’s found a couple particles that are suspicious under the microscope, but nothing definitive. He plans to test both his water and deposition samples in the next couple of months.

To test the samples, he will have to use hydrogen peroxide to digest the organic matter in the sample, leaving him with only the particles that are suspected microplastics. He can’t say with certainty that the particles remaining are actually microplastics until he tests them using techniques called Raman spectroscopy or Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR).

Both techniques use specific kinds of light that are sent through the sample. They emit back a unique light pattern that can be used like a forensic examiner uses a fingerprint. This technique can identify the specific substance without destroying the sample.

“If we know what kind of plastics there are, it’s a way for us to find their source,” says Xiong.

The tourism that the Flathead Valley relies on for economic stability could be a factor. Xiong found that tourists were an important source of microplastics in Qinghai Lake, which is the largest lake in China, in the Tibetan plateau.

Determining something about the source may help to reduce the consumption of whatever seems to be the most prevalent contributor. If Xiong finds mostly microfibers, the source could be laundry. If he finds particles it might be bags or bottles.

Xiong was hopeful in coming to America that people would be more environmentally friendly than they are in China. He was surprised that plastic bags were free at all the stores here. “In China we have to pay for the plastic bags, so people want to reduce or reuse the plastic bags, but here it’s all free,” he says.

Flathead Lake Biological Station education coordinator Holly Church says she’s equally surprised to see how plastic is used in the Flathead Valley. She helped with an “adopt a highway” cleanup in front of the Bio Station in late May of 2018. “I’m horrified how much plastic that is just along our roadways,” she says. “If you just drive anywhere along here there’s plastic flapping on all the fences. It’s everywhere here.”

The trash along the highway 35 roadway blows into the lake.

Church walked along the shoreline of the lake for a short distance in May when the water was low and collected a startling amount of trash that had washed up out of the lake. She collected a whole box full, including the cap to a firework rocket, plastic bags, monofilament fishing line and pieces of PVC pipe.

Church has also pulled up plastic in the Flathead Monitoring Program’s plankton net while out sampling.

Before Church moved to Montana she lived and worked as a science teacher in California and Hawaii. These states have both taken the initiative to start getting rid of plastic, at least from stores.

Hawaii has gotten on board, because they are starting to see pretty dramatic effects. Church says she has a handful of “confetti sand” that she got off a beach in Hawaii. It’s a jar of sand mixed with colorful plastic particles.

“I don’t think it’s something that we should continue to have in our environment,” Church says. “Now that we can’t recycle plastic in the valley, it’s even more of an issue. There’s got to be some kind of awareness increase.”

Church is planning to set up a citizen science community lake cleanup project based at the Flathead Lake Biological Station. It will help combat the amount of trash that is making it into the lake. Tribal natural resources information and education program manager Germaine White says that the tribes are hopeful that they can partner with Church in this effort.

A collection of trash found by Holly Church as she walked along the lake shore in May.

Church thinks the community will be quick to pitch in when they become aware of the extent of the issue.

Involving schools in cleanups would raise awareness as well according to Church. With the Bio Station’s expanding K-12 education program, there may be room for more pollution awareness in the curricula. When kids are young they form a lot of the habits they will carry into adulthood.

Church agrees with Xiong that the oceans are receiving most of the attention. She’d like to see freshwater system get more awareness, especially since there are far fewer cleanup programs for freshwater systems than for oceans.

Regardless of what Xiong’s findings show when he analyzes his samples, there are things that can be done to reduce trash that goes into Flathead Lake. Reducing washes of synthetic clothing, using tie downs or cargo nets to secure items in the back of vehicles or on top of cars, or even grabbing fewer plastic bags at the grocery store are all simple ways to help keep the lake blue and pristine into the future.