One Man’s Legacy to stop Flathead Lake’s Shrinking Shoreline

By 2020 Ted Smith Environmental Storytelling Intern Kelsea Harris-Capuano

Strolling down to the shorefront of Flathead Lake was Dr. Mark Lorang, where moments before a young cinnamon colored black bear had stood. The wildlife encounter prompted Lorang to launch into a story about a wolf he recently saw up at his cherry orchard.

But Lorang didn’t come to chat about wildlife. As a physical lake ecologist, he came to check out his handy work, a new erosion control beach at the Flathead Lake Biological Station (FLBS). This beach is one of the latest in his 30+ years of beach design and construction, and he’s still excited about his work.

Former faculty at the Bio Station, Lorang’s expertise includes water and sediment movement; erosion and deposition; and resultant geomorphic features. He has conducted extensive research on waves, wave power, and their ability to move sediments and change a shoreline. He has worked on lakes, rivers, estuaries and coastal areas.

Lorang has been interested in beaches since he can remember, and has devoted much of his professional life to understanding and remedying their disappearance on Flathead Lake. Lorang’s father, a now-retired teacher, took classes at the Bio Station and lived in one of its cabins in 1959. Loving the area, it was his dream to own land by the lake and eventually he bought a cherry orchard near Yellow Bay.

As an only child Lorang avoided working at his dad’s cherry orchard by spending much of his time down at the lake exploring, observing and investigating. He liked skipping rocks, watching the waves and wandering the shoreline.

He remembers how much more beach there was back then. He said he could walk for at least a mile or two unhindered by anything.

When Lorang was a teenager someone bought the property next door and immediately started cutting down trees. Lorang was devastated to see the old growth trees taken out. A few years later while Lorang was pursuing a BA in geology at the University of Montana, that neighbor built a seawall. Within two years of the seawall’s installation the Lorang’s beach was completely eroded away.

“Trees were falling in the lake and he was telling us we were idiots for not building a seawall. That was when I really started diving into how to stop the erosion,” he said.

Motivated by his interests in wave dynamics and erosion on Flathead Lake, Lorang went on to earn an MS and PhD in Oceanography from Oregon State University. His MS thesis was about shoreline erosion on Flathead Lake and his PhD dissertation was about the wave dynamics of gravel beaches.

Lorang was hired in 2000 by Dr. Jack Stanford, FLBS Director at the time, as a Associate Research Professor. His job was initially funded by Montana Power Company, the company that built and operated Kerr Dam at the time. The dam and its operations were up for relicensing and they had to assess and mitigate for past and potential future damage which included erosion. Lorang eagerly jumped at the chance to work on the project.

A History of Erosion Damage

The Se̓liš Ksanka Ql̓ispe̓ Dam, formerly known as Kerr Dam, was built by Montana Power in 1938 for hydropower production. The dam controls Flathead Lake water levels, which fluctuate as much as 10 feet throughout the year due to snowmelt, power production demands and recreational purposes.

During June, the lake level is brought up and then held at full pool through Labor Day for summertime recreational users. Late summer and early fall is when the most powerful storms come through the area creating the largest waves and causing the most erosion damage.

In a short report on Flathead Lake’s wind and waves, FLBS Associate Director Tom Bansak, described how wind speed is the primary driver of waves. Bansak said that the amount of time (duration) that wind blows over a certain distance (fetch) determines wave height.

Bansak continued that a maximum wave height for Flathead Lake can be calculated by using recorded wind speeds and the fetch of Flathead Lake which is 28 miles in length. Using those calculations, Flathead Lake waves can be as high as 1.5 meters or almost five feet.

With lake levels highest during the stormiest part of the year, waves of up to five feet have the potential to severely erode unprotected shorelines.

In a recent conversation, Stanford said that the dam’s original mandate was solely about hydropower, but the high water level in summer became something recreationists and shoreline owners liked and expected. This led to an agreement or Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in 1964 between the Army Corps of Engineers and Montana Power Company (MPC). The MOU stated that water would be brought up to full pool from mid-June through July, and stay within the top foot through August.

This MOU was filed with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and became a part of the dam’s operating license, regardless of the dam owner which later became PPL Montana and is now the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT).

The Bio Station was founded before the dam was built, which means there is ample long-term data comparing before and after conditions of the lake and its shoreline.

Stanford, during his time at the Bio Station from graduate student in 1972 through 2016 when he retired as FLBS Director, personally witnessed extensive shoreline and habitat loss on Flathead Lake due to erosion.

Stanford remembers a forest, now completely gone, that used to sit on Flathead Lake’s North Shore near the Flathead River Delta. Now part of a Waterfowl Production Area, the North Shore has been hit particularly hard by erosion, and he said it was a dramatic change to witness.

Shoreline erosion also affects water quality as it causes inputs of both sediments and nutrients into the water, and the Bio Station identified erosion along the North Shore as a source of sediment and nutrient pollution in Flathead Lake.

Deeply concerned about the impact the erosion would have on water quality, habitats and lake shoreline, the Bio Station with Lorang leading the charge, set out to understand exactly how erosion worked and what could be done.

Lorang focused on wave power and dynamics, and his work led him to the conclusion that lowering the high water level of the lake by just one foot would significantly reduce further erosion. He and Stanford published a scientific paper to that effect in 1993 and thought the public would easily adopt such a seemingly simple solution.

“Over the years there has been really full-hearted cooperation between the station and the general public. This idea, pulling the lake down a foot caused a lot of people to go off the rails. People had built docks out based on the full pool elevation. And even though those docks were routinely destroyed by waves, there was a huge, I mean, huge outcry about that,” Stanford said.

If water level operation was going to remain unchanged, Lorang needed another solution for erosion damage, which ultimately led him to his gravel beach work. Picking up a few rocks from the beach that had shifted during a week with a few storms, he noted the changes, gravel piled up here, debris there. He took a few photos.

“I might have more photos of beaches than my kids,” he said laughing.

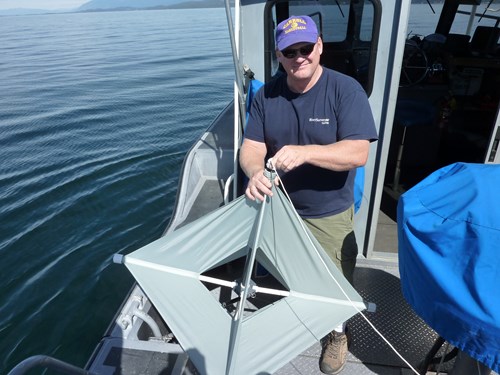

Mark Lorang conducted important research at FLBS in the 1980s through 2016.

An Unheard-of Solution

Gravel beaches as a way to protect shorelines from erosion is “designing by nature” Lorang said. He builds beaches that mimic the characteristics of naturally occurring beaches.

His beaches are made of varying of gravel and cobble that absorb the force of waves while forming a dynamic protective barrier or berm. He said beaches dissipate incoming wave energy more effectively than riprap and seawalls, the standard methods for erosion protection.

The absorption of wave energy will shift the gravel around, reshaping and changing the beach. Also called a dynamic equilibrium beach, the changes are just a part of a resultant balance between the aquatic and terrestrial environments.

In one of Lorang’s early reports on the use of gravel beaches as erosion protection, he stated that the movement or transport of material was a purposeful design element and shouldn’t be viewed as damage. This is very different from the rigidity of a concrete sea wall or large boulder field.

Even though that report was from a conference in Seattle almost 20 years ago, Lorang’s technology, and the “designing by nature” method, is still not well known or commonly practiced. He has been publishing papers, experimenting with and building beaches, and trying to disseminate his ideas to the public for over 30 years.

Leap of Faith Leads to Slow Success

Bigfork business owner and long-time member of the Montana state legislature, Bob Keenan was the first to reach out to Lorang about building a beach on his property. Keenan bought property on the North Shore of Flathead Lake in 2000 and four years later a particularly bad fall storm season eroded away a huge chunk of his shoreline.

Alarmed by his disappearing shoreline Keenan went looking for a solution. He heard that Lorang opposed seawalls and was offering an alternative solution, so he gave him a call.

Lorang was incredulous when Keenan told him he thought he had lost over 40 feet of shoreline in a single storm event. Lorang was amazed at what he saw, and his measurements confirmed Keenan’s observations. His work was cut out for him.

Despite skepticism from the local community, Keenan was eager to work with Lorang and try something different. “They told me I was the biggest fool in the world. Everybody said pour gravel and rocks into the lake and they’ll disappear,” Keenan said.

Lorang’s work on Keenan’s property on the North Shore performed well, and after several years other concerned owners and agencies saw how erosion control beaches could protect the North Shore’s particularly biodiverse and cherished sections of lake shoreline.

The North Shore of Flathead Lake stretches for about seven miles between Somers and Bigfork. It is mostly undeveloped shoreline, wetlands and adjoining uplands. Most of the wetlands and shoreline are now part of the Flathead Lake Waterfowl Production Area (WPA) managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS).

Since the North Shore has seen particularly bad erosion damage, private property owners over the years have worked with USFWS to conserve and protect it, and a number have sold their properties to USFWS.

Kerr Dam’s FERC relicensing process initiated in the mid-1980s required mitigation of erosion caused by dam operations. PPL Montana, the dam owners after MPC, hired engineers who designed a giant concrete seawall to be built across the entire North Shore. The seawall design included riprap placed on top. The project cost was estimated around $6-8 million.

After the North Shore seawall project was stalled for years due to the high cost and opposition from the community, PPL Montana consulted with Lorang to design a gravel beach to cover the seawall for aesthetic purposes. Lorang persuaded PPL and the USFWS to consider his erosion control beach designs instead, which was estimated to cost about $1 million.

In 2008, working with the USFWS and PPL Montana, Lorang oversaw construction of about 4,500 feet of beach along the North Shore WPA east of the Flathead River. A connecting berm extends 1,200 feet or so up the Flathead River's eastern shore.

More than 8,500 feet of the North Shore are now protected by Lorang beaches.

A Future of Erosion?

In 2015 the CSKT became the first Tribes in the nation to own a major hydroelectric facility after paying a little more than $18 million to own the Se̓liš Ksanka Ql̓ispe̓ Dam (formerly Kerr) outright.

Now further erosion mitigation and land restoration caused by the dam is their responsibility.

Brian Lipscomb, President and CEO of Energy Keepers Inc. the tribal corporation that manages the dam, said that the facility is managed according to the federal operating license from FERC.

“We have the same operating requirements as the previous owners with regards to the river and the lake,” Lipscomb said.

Managing water levels is much more complex than pushing a button. Since Flathead is a natural lake with mainly unregulated rivers upstream, and the dam only controls that top ten feet of water, Energy Keepers carefully calculates and predicts conditions to maintain the appropriate water level.

This includes anticipating electricity demands, seasonal weather conditions like large spring snowpack or fast melt off, and Hungry Horse operations, another dam north of Flathead that controls fluctuations of the Flathead River Lipscomb said.

Lipscomb said they don’t anticipate making any changes to the current operating license. While a relief to some, in terms of shoreline erosion this is bad news. Since water level management of Flathead Lake for the foreseeable future will remain unchanged, erosion damage around the lake’s shoreline will continue.

Over 80 years of dam operation and significant erosion is still occurring Lorang said. People are still applying for seawall and riprap permits for protection. The shoreline has not reached a balanced or equilibrium state.

Lorang is exasperated with the slow acceptance of gravel beaches as erosion control. To him it’s the ideal solution, and decades later he’s still in conversations with engineers who claim that his beaches won’t work.

“Then how is it possible that natural beaches even exist?” he said.