Deep Dive into FLBS: A Bio Station History of Art and Science

Written from the perspective of FLBS Media and Information Specialist Ian Withrow, each "Deep Dive into FLBS" column features entirely original content and provides a behind-the-scenes glimpse at Bio Station science, researchers, partners and programs. Future installments are scheduled to be published by the Bigfork Eagle the third Wednesday of each month.

For as long as I can remember, there’s been this notion in the popular consciousness that art and science are independent, if not opposing areas of study. You have the right brain and the left brain. The creative and the logical.

When I was in school, art class was always a peripheral priority. It was something we did on Fridays before a long weekend or an elective that helped round out the spring schedule. Science subjects, meanwhile, were stringently required. And yet I can’t think of a single science class that didn’t ask me to create no less than thirty colored pencil drawings to illustrate what I had learned.

“See those mitochondria in the microscope? I want you to draw them.”

“See the way water is sloshing back and forth in this tank? Okay, I want you to draw it.”

“See the intricate, three-dimensional viscera of this dissected earthworm? When you finish dry-heaving I want you to draw it.”

Sometimes I wonder if I would’ve received better grades in those classes if I’d had the opportunity to practice my art skills (although my seventh grade representation of an earthworm’s gonads is breathtakingly accurate, and I don’t care what my wife says, it’s going to take a heck of a lot more than an ambivalent crayon mosaic from my one-year-old daughter to dethrone those gonads from their rightful spot on our fridge).

The truth is that art and science have always been fundamentally intertwined. Think Leonardo Da Vinci. And if my earthworm gonad portrait isn’t enough to convince you, then how about the long history of art and science at FLBS?

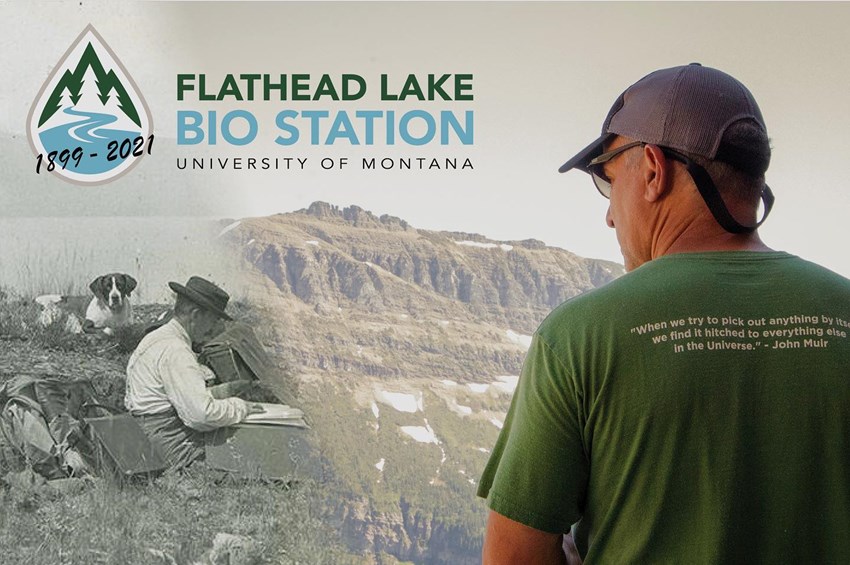

Bio Station scientists and students have conducted research in the rugged Flathead Watershed for over 120 years. The first backcountry outing took place in 1899, the year the Bio Station was founded in Bigfork. Photographic technology was around back then, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that it became affordable, effective, and compact enough to be a good option for field work. Until then, cameras were large and cumbersome tools that broke easily, malfunctioned often, and even required a horse to carry them out into the field. For most of a century, scientists and students at FLBS relied on their own artistic talents to document their discoveries.

Morton J. Elrod, the Bio Station founder, was quite skilled with a sketch pad. Illustration classes were listed alongside ecology courses at FLBS up through the 1960s to help aspiring researchers better understand the artistic concepts of texture, space, and form. Famous artists and scientific illustrators from across the country would visit FLBS to draw newly discovered plants and animals, documenting innovative FLBS research for a nationwide readership. Such artists included best-selling author and environmental illustrator Anna Comstock, who published the world-renowned book “The Handbook of Nature Study” in 1911 (still in print in its 24th edition) and whose artwork presently resides in the FLBS Museum at Yellow Bay.

Obviously, technology has advanced since those days. The monolithic shadow of the smartphone grows long, and any practical necessity for illustration skills in field work seems to have gone the way of the fountain pen. But that doesn’t mean the connection between art and science has waned at FLBS. Quite the contrary—under current FLBS Director Jim Elser, the Bio Station’s artistic investment remains as strong as ever.

Since 2018, FLBS has partnered with Missoula-based Open AIR Montana to host nearly a dozen artists-in-residence at our Bio Station. These visual artists, cartoonists, painters, writers, and poets spent anywhere from a week to two months living in FLBS cabins, working directly with our scientists, and engaging with important freshwater monitoring and research. These interactions helped inspire incredible pieces of artwork that invite fascinating new perspectives on the ecological inner workings of the Flathead Watershed.

But you don’t have to take my word for it. Currently on display at the Bigfork Art & Cultural Center in downtown Bigfork, the “Scene + Unseen” art exhibition presents a wonderful selection of work created by our Open AIR Montana artists-in-residence. The exhibition also highlights the works of local painters who participated in our 2020 Plein Air Painting Workshops, which were organized and led by 2020 FLBS Open AIR artist-in-residence Sandra Marker. The exhibition ends this Saturday (9/25) at 5:00pm, which means you have only a few days left to stop by and see Flathead Lake’s zooplankton community portrayed in oils, glacial snowmelt records commemorated in finely molded paper, or the Boulder 2700 Fire experience penned in the panels of an emotionally potent comic strip.

What’s not on display is the significant impact these artists have had on FLBS scientists, who as a result of our artist-in-residence program have been granted new ways to examine their own research, data, and investigations into our natural world. After all, when you really stop and think about it, artists and scientists are compatible explorers cut from the same curious cloth, aren’t they? They may speak in different dialects, and examine the same detail through a different lens. But even though they negotiate their seemingly opposing paths, their journeys are equally tedious and just as sincere, and when they look out at the breathtaking beauty of the Flathead Watershed, the questions they seek to answer are almost always the same:

How do we best understand this remarkable place, and where does our humanity fit in?