Growing up at the Flathead Lake Biological Station, Then and Now

by Heather Fraley, Environmental Science and Natural Resource Journalism Intern

For a young Ginny Miller, summer in Montana was synonymous with freedom and adventure. It meant endless days of unsupervised exploration with other kids. It meant row boats and swimming; raiding a pop machine and playing ping pong. It meant hiking and camping among towering ponderosa pine trees, building forts out of driftwood and getting into general mischief as only kids can.

Miller grew up at the Flathead Lake Biological Station in the mid 1960’s through the 1970’s. Not only is it an education and research station, it’s also been a home for a lot of people. The grounds of the Biological Station witnessed a great deal of childhood experiences, watching each new generation of kids come and go.

Growing up at the Bio Station left its mark on everyone who experienced it. For some, it influenced where they decided to live, the careers they chose or even who they shared their lives with.

“I really think it changed our lives,” says Miller.

Miller is in her late 50s now, but as she ushers me into her home in an upscale neighborhood in Missoula, Montana, traces of those idyllic childhood summers still surround her. Photos from the 1960’s and 70’s are sitting on her coffee table.

Growing up at FLBS, Ginny Miller always felt as though the people at the Station were like a big family. She was also obsessed with horses. During one particular birthday, a graduate student gave her a horse's jaw bone that he'd found during his research on Wild Horse Island. Some 30 years later, Ginny still has that jaw bone, and recently married the once-graduate student who gave it to her.

She goes into the next room to get another memento of her time at the Bio Station to add to the pictures, and comes back holding a piece of a horse jaw. The rough, grayish-white bone is a reminder of the place that first introduced her to Montana. She’s kept it all these years.

Some of her favorite memories are from those summers at the Bio Station.

“Those were the best years,” says Miller, as she flips through the pages of a photo album.

Being at the Bio Station made her feel like she was part of a big family. In particular, she remembers either her 9th or 11th birthday when she was obsessed with horses. The kitchen staff made her a full sheet-cake with a picture of Flathead Lake on it, and plastic horses running across it.

To top it off, a graduate student brought Miller the horse jaw from Wild Horse Island, an island in Flathead Lake that boasts a small feral horse population. Wild Horse Island is a special place for Miller. She even met her husband there while working as a wildlife technician one summer for renowned Bio Station osprey researchers Don and Doug MacCarter.

Miller’s father, Orson, was a researcher from Virginia Tech who studied fungi and mushrooms, and taught summer classes.

Miller spent every other summer at the Bio Station from the mid 1960’s when she was only 5 years old, to her senior year of high school. Miller’s parents would load up their family in Blacksburg, Virginia and come to Montana for the summer.

The other faculty and staff would bring their kids back year after year. It created a family reunion atmosphere, and a group of kids that would roam the station.

“It was pretty much a Shangri-La for kids, because our parents trusted us to stay in a band,” says Miller. “Kind of a little wild pack.”

The kids learned to be very self-sufficient. They could entertain themselves for hours without adult supervision or iPhones. They traveled the grassy corridor down to the beach over and over. They fished off the dock in front of the Elrod Laboratory with canned corn as bait. They played and swam together every day, and experienced life’s milestones together. The director at the time’s youngest son even took his first tottering steps in the old Quonset hut dining hall.

The dining hall was a kid’s paradise. For a while, it was run by a matronly lady from the Phi Theta Kappa house on the University of Montana’s main campus. She brought a few of the fraternity boys with her to help with the cooking and dishwashing.

A siren echoed across the Bio Station grounds to announce every meal, and the kids lined up outside the dining hall as if they were waiting at the gate to a carnival ride. No child ever went unaccounted for. Once inside, they piled whatever they wanted onto their plates, and dispensed milk and pop in endless quantities.

The kids got into their share of mischief. The pop machine next to the ping pong table in the student center was so old, and their arms so small, they could just reach their hands up in and pull bottles out for free.

Miller flips through a couple more pages of the album, exclaiming at several black and white photos. “That’s my dad. That’s his graduate student; I recognize these people,” she says.

She points to one photo, a black and white picture of a man leaning over a sink in a lab. “That’s Dr. Solberg,” she says. Dr. Richard “Dick” Solberg was the Bio Station’s director at the time the Miller family first started coming. He was well-known for getting funding, and was responsible for the new Elrod Lab built in 1968 where the old “brick lab” had been. He had four children. Tina Solberg was Miller’s age, and Jenanne Solberg was the same age as Ginny’s older sister, Andrea “Andy” Miller.

Former FLBS Director Dick Solberg (middle) stands with his children Sannan (left) and Jenanne (right) on the shoreline of Whitefish Lake in the summer of 2018.

Jane Solberg, the matriarch, crammed a tiny cabin full with her whole family. There were only two rooms where she had to fit five beds and a crib.

She washed endless soiled diapers in the wringer washer and even bathed her young son Sannan in the washer’s rinse tub.

There was no bathroom in their cabin (Bio Station cabins still don’t have private bathrooms), but they had electricity. Records often spun around their ancient turntable. “We had literally three records,” says Jenanne as she sits around her parents dining table in their home in Whitefish, MT. “Big ‘ol vinyl platters,” adds her father Dick Solberg, smiling.

The voices of the Limelighters, Roger Miller, and Jimmy Rogers, echo through the memories of the Solberg kids. Through Children’s Eyes was the favorite album of the three.

“Any one of us siblings can sing every word of every song on that album,” says Jenanne laughing.

Andy Miller and Jenanne Solberg started a laundry business they called Jenandy’s Laundry. They washed the students’ clothes in the Bio Station’s old wringer washing machine for 25 cents a load, and ironed clothes for just 10 cents more.

Jenanne and her brother Sannan agree that the trip to “the point” was one of the most memorable things about childhood at the Bio Station. It was a quarter of a mile hike to the west edge of the bay. But as anyone who’s ever been back to their elementary school as an adult knows, things seem a lot bigger when you’re small.

“We thought that was miles,” she said. “We’d pack lunches and take little backpacks. We honestly thought that was the end of the earth.”

The Solbergs have continued to maintain a close relationship to the Bio Station. Sannan Solberg’s now 18-year-old twin daughters went to the station on a field trip for school, and introduced themselves to the current faculty and staff. Dick and Jane always attend the annual Research Cruise, and many other Bio Station events.

The Footes were another family that came year after year for 14 summers, bringing their entourage of four children from Ohio in their old station wagon. Dr. Benjamin Foote was an insect researcher at Kent State. He stored peanut butter sandwiches along with bug samples in his lab fridge, and he kept all the kids busy by giving them bug collection nets and killing jars.

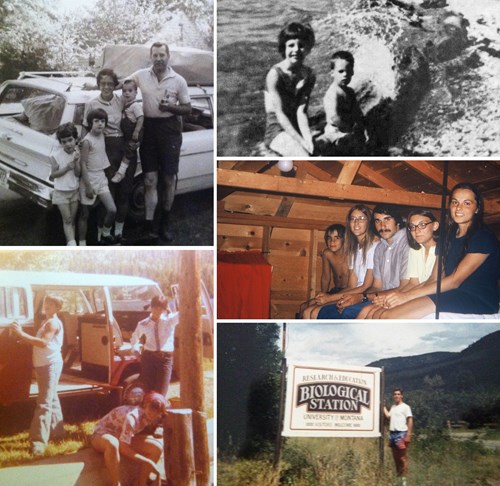

Grant (Foote) Frericks (pictured as a toddler in his mother's arms as a toddler in the top-left photo, and as a young man next to the FLBS sign in the bottom-right photo), spent the summers of his formative years at FLBS. For over a decade, his parents packed the family up and made the drive to FLBS from Ohio, where his father, Benjamin Foote (pictured on the far right in the top-left photo), was an insect researcher at Kent State University.

There were rites of passage and important self-realizations for kids at the Bio Station. One rite of passage was “The Rock.” “The Rock” was a large rock just about 25 yards out from the beach. It was a big achievement to swim to the rock and stand up on it. Grant (Foote) Frericks still remembers the first time he was able to make it out to “The Rock.”

Another rite of passage was to construct forts. Together with the other kids, Frericks started building the driftwood forts that would be handed down through successive generations of Bio Station kids.

In addition to these rites of passage, many kids also had important realizations at the Bio Station, and Frericks was among them.

He went to an after-dinner seminar put on by a gay and lesbian rights group from the main campus in the 70’s. He vividly remembers that experience as a ten-year-old as a turning point in realizing that he was gay.

Although he lives in Ohio, he loves Montana, and he’s brought his husband Matt Frericks back to visit several times. A lot of his dad’s graduate students from Kent state that were at the Bio Station still keep in touch and come over to their house.

Faculty and staff children still visit the grounds or call the Bio Station home. 31-year-old Teal Potter just finished her PhD in plant ecology at University of Colorado Boulder in 2018. Soon she’s headed off to become a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Potter grew up at the Bio Station from 1986 to 2002. As a kid, she made sand castles on the volleyball court, and she rebuilt what she calls the “driftwood fort” that Miller’s cohort started in the 60’s. The fort has been added to by generations of kids. Potter even took her boyfriend back to see the fort even though it had collapsed. “It was this magical fort I inherited,” she says, “this prebuilt fort.”

Potter lived at the Bio Station year-round as the daughter of the facilities director. She says that growing up there influenced her to become a plant ecologist, and gave her a leg up in the scientific field. She remembers watching all the scientists she grew up around and thinking that she wanted to do that.

“I always thought it was a cool job,” she says, “one, because they got to work outside, and two they had the freedom to ask questions and explore the things they wanted to. They got to travel too.”

She also got so much exposure to graduate students that she knew what grad school was all about before she got there.

Teal Potter, who lived at FLBS from 1986 to 2002 as the daughter of the facilities director, recently finished her PhD in plant ecology at the University of Colorado. She credits growing up at the Station with sparking her scientific interest and giving her a leg up in the field.

The Bio Station had an increasing influence as she went on in her career. She worked in the lab at the Bio Station for a couple of winters, acid washing glassware. She also took some summer classes. She remembers how weird it felt to go from living at her parent’s house to living in one of the cabins as a student. “It was like, whoa I’m finally like that adult that I was so in awe around,” she says.

Her connections from the Bio Station helped jump-start her career. She got letters of recommendation from former Bio Station Director Jack Stanford and another couple of faculty members for a competitive undergraduate internship working on alpine plant communities in Colorado. She credits that internship with influencing her decision to study plants.

She graduated from college in 2009 during the most recent recession, and her experience set her apart in a tough job market. She quickly got a job as a lab manager with full benefits.

Currently, the facilities director is Eric Anderson. He started raising his two children at the Bio Station in the 2000’s after starting work at the station in March of 1999. He’s been there ever since. “Hard to want to leave when you have a house on the beach, and what a great place to raise kids, I thought,” he says.

His two children, daughter Kenna, age 13, and son Braden, age 15, were raised at the Bio Station. They are excelling in school, and he attributes some of that to their unique upbringing.

“I think the full immersion they got certainly gave them a leg up, at least in the sciences,” he says.

Kenna and Braden are very self-sufficient as a result of their childhood. They learned to boat and sail by themselves, and joined their dad on hunting trips with his Bio Station graduate student friends.

“I felt like it was a privilege to raise them in this environment,” says Anderson. “I mean the place is so clean, so pure, so untouched, so natural, so wild still, that no matter what they do now, at least they have this.”

His daughter Kenna has been influenced by all the science she’s surrounded with. She says she wants to be an environmental engineer. “They try to get people to work in harmony with nature,” she says.

Today there is an even younger generation coming up behind Anderson’s kids. Kenna Anderson sometimes babysits Bio Station employees Matt and Holly Church’s two daughters Annabelle, 9, and Hadley, 6.

“They’re budding little scientists,” says their mom Holly Church, Bio Station education coordinator.

“They both love coming here in the sense that they get to see things and learn about things that they normally wouldn’t.”

The two girls come on the weekends with their parents to use the canoes, and they enjoy the gatherings hosted by current FLBS Director Jim Elser at his Bio Station residence a few times a year. At these socials, all the faculty and staff kids get together and play.

Among the other faculty and staff kids are assistant director Tom Bansak’s son, researcher Cody Youngbull’s two boys, researcher Shawn Devlin’s three boys, Researcher Tyler Tappenbeck’s son, Freshwater Lab Manager Adam Bauman’s two boys, and Research scientist Phil Matson’s kids. Matson’s son is following in the footsteps of the Bio Station kids of the 60’s, catching fish off the dock on a homemade fishing pole.

The circle of connection to the Bio Station continues for Ginny Miller. Miller kept coming back year after year, continuing to go through life’s milestones. She shows me a picture of her pregnant on the beach. She introduced her daughter to the Bio Station when she was young.

Ginny Miller sunbathing while pregnant on the Flathead Lake shoreline during one of her visits to FLBS years ago.

She and one of her two sisters moved to Montana as adults because of their experiences. Thirty years after meeting her now-husband Jeff and working together all summer, she reconnected with him and they got married. One of her bosses from the job on Wild Horse Island, Doug MacCarter, still owns a place on the island. Miller and her husband remain friends with him. Miller recently reconnected with Grant Frericks online.

For her, the indelible mark of the Bio Station has always remained.

“It was kind of an amazing place all and all,” she says.