A Lasting Impression: Retiring Researcher’s Final Project Aims to Capture a Lifetime of Experiences on Film

By 2022 FLBS Ted Smith Environmental Storytelling Intern Joshua Moyar

Jim Craft sits hunched over a microscope in the Flathead Lake Biological Station’s aquatic research lab. Carefully, he studies the image, projected 560 times its actual size.

“I have no idea what this is,” he says to his undergraduate intern Brooke DeRuwe, a University of Montana student in Environmental Science and Sustainability. “I want a picture of that.”

Craft has been diligently studying Flathead Lake’s phytoplankton, microscopic floating plants, at FLBS for nearly 35 years, and even now, a mere two months from retirement, he still finds himself surprised by the more than 1,000 species of algae that inhabit Flathead Lake’s 197 square miles. This summer, Craft’s goal is to photograph as many prominent species as he can before he steps down from his position as a research scientist.

The phytoplankton Craft is looking at, dubbed “unknown sphere-17,” is just one of the dozens already logged in his photo archive, a project that will become indispensable to the Bio Station as it prepares to lose one of the greatest minds in algal taxonomy.

Most of what Craft has learned about these charismatic little cells was picked up in the very same lab he works in now, more than 30 years prior. After graduating from high school in Delaware, Craft was sure he wanted to work in the field of marine biology. He ended up completing a degree in aquatic wildlife biology at the University of Montana in 1986 and started at the Bio Station just two years later.

FLBS Scientist Jim Craft retires after over three decades of monitoring the Flathead Watershed.

“My first six months here, I worked in the lab,” Craft said. “They had this huge backlog of carbon to analyze, and the carbon analyzer was old school. You break the ampule and bubble it for three minutes, and then run it through the analyzer. So I had three minute breaks all the time. I had a microscope set up next to the analyzer, so once I had that ampule in there and hit my timer, I started looking at plankton. I just sat there and looked at algae for six months.”

“As soon as he looked at them under a high-powered microscope, he was hooked,” said Bonnie Ellis, a long-term Bio Station lake ecologist, now retired.

Ellis was a mentor to Craft in their 27 years of overlap at the Bio Station. According to Ellis, it was Craft’s enthusiasm that made him stand out among his peers.

“I remember even when the lake froze over and we had to head out on skis he was excited,” she said. “We were pulling our equipment on sleds doing monitoring around 1989, and on one trip we ran into a long crack in the ice and were worried about having difficulties getting back, but Jim never had any qualms about going out. He was just so excited about doing it.”

Craft’s increasingly bountiful knowledge of Flathead’s algae quickly came to use when Ellis brought him on to the Bio Station’s long-term Flathead Monitoring Program (FMP), where he remained all his years at the Bio Station. Since its launch in 1977, FMP has been one of the flagship projects at FLBS, generating one of the world’s best lake datasets, and truly earning the Bio Station’s nickname, “Sentinel of the Lake.”

Fifteen times each year, Craft and fellow FLBS researcher Tyler Tappenbeck go out to the deepest point of Flathead Lake to measure and sample just about everything—temperature, light intensity, nutrient concentrations, both phyto- and zooplankton concentrations, rates of photosynthesis—all at different depths.

FLBS Scientists Tyler Tappenbeck (left) and Jim Craft (right) collect the first samples from the long-term Polson Bay Monitoring Site in 2019.

Putting all this information together and comparing it with previous years helps paint a picture of what exactly is happening to Flathead Lake over time. Through regular monitoring, scientists can detect changes in the lake before they become problems.

“I call it the crown jewel of the Flathead Lake Biological Station,” said Matt Church, the FLBS Professor who currently oversees the monitoring. “It's the program that I would argue the station is best known for. It's super important for helping us understand not only this lake, but it broadens our understanding of all lakes.”

Jim Elser, FLBS Director of six years, agrees.

“It’s the foundation for anyone who works in the lake,” Elser said. “Being able to draw on that, without having to get your own baseline of everything, is huge. It's important for anyone doing research, but also as a mechanism to communicate to the public … We need to be able to show them if the lake were deteriorating. This is the evidence that would be brought to bear if the lake was going the wrong direction.”

Fortunately, the data Craft has been collecting for the bulk of his career shows that Flathead Lake remains clean, clear, and healthy. Unfortunately, replacing Craft, who FLBS Director Elser says “knows more about Flathead Lake than any person alive,” is both necessary and challenging.

“Longevity in personnel is something that is absolutely critical and hard to replace in a time series like FMP,” Church said. “You could imagine that in the middle of a time series if we started using a different type of instrument, or in this case, a different person, there's some likelihood things could change. That makes it very difficult scientifically to interpret the results of the time series, so that longevity is really, really important. This station has benefited enormously from Jim [Craft] having been in that role for so long.”

Beyond filling Craft’s role on FMP, finding a phytoplankton taxonomist is borderline impossible in this day and age. Elser thinks there may only be a couple dozen in all of North America. According to Craft, they’re “few and far between. All the ones I know are retired.”

“I don’t run into many people who are really into algae,” Craft said. “They aren’t as excited about it as what eats it. It takes just the right person to get into taxonomy. So many people are more interested in how things link together. They don’t really care who he [the alga] is. They care more about the combined outcome. I like to know what species are doing. I like species investigations.”

Of course, Craft’s phytoplankton photo ark is, though not quite a solution, a vital tool in the future of algae identification at FLBS, and maybe even across the wider scientific community.

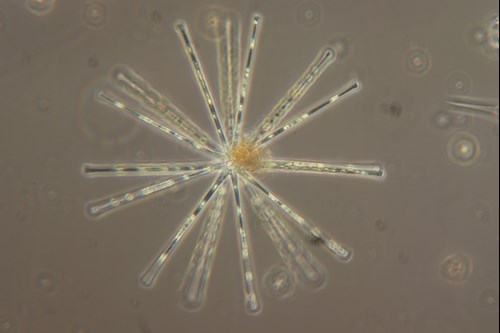

A recently captured image of asterionella formosa taken at 20X magnification.

“Whoever comes next will be able to go back and look at those pictures and say, ‘Oh, this is what Jim called ‘X,’” Elser said. “They’ll say, ‘Oh, what is that? It's either A, B, or C,’ and then they’ll look at the photo archive and see what Jim called it.”

Craft credits Ellis with beginning the archive. She initially took pictures of Flathead Lake phytoplankton under an electron microscope back when she was completing her master’s project in the early 1980s. While the photo archive in its final form has just begun, it has made leaps and bounds this summer. Five weeks into photographing, Craft, with DeRuwe’s help, has taken pictures of about half of the species he hopes to. Unfortunately, the further into the project the pair goes, the harder it becomes to find the missing species in countless archived samples.

Still, the easy-going Craft isn’t too concerned.

“The good news is that this camera is mine,” Craft said. “I have my own microscope. My own house. I do this anyway. So over the next couple of years I'll be filling in the holes when I can.”

But for now, Craft is getting ready to leave research behind this coming September to spend time with his family and his golf clubs. As he prepares to head out, the rest of the Bio Station’s staff prepares to lose him.

“He’s an institution,” Elser said, “not just someone that people rely on for great technical and scientific advice, but someone who's seen it all happen on the lake, who knows how to read the lake, who knows how to handle different situations that come up when you're sampling. All of those things are going to be hard to replace. And then, of course, he's just a super great guy. When I bring my classes out on the lake and Jim’s the captain, I know that the students are going to learn.”

Jim Craft demonstrates sampling techniques for undergraduate students enrolled in the FLBS Field Ecology course.

Craft’s impact on young scientists cannot be understated. During his decades at FLBS, he has likely trained and helped mentor nearly 100 interns and graduate students, as well as educated thousands of undergraduate students about Flathead Lake and our freshwaters.

This summer, Craft has inspired another generation of algae-lovers. Since beginning her work with Craft in June, 21-year-old DeRuwe has started sharing the pictures they’ve taken on her Instagram, a series she calls “phytoplankton of the day.”

“Just seeing how excited Jim is about phytoplankton has made me excited about phytoplankton,” DeRuwe said. “I’m trying to take the excitement that he made me feel and share it with my friends.”

DeRuwe and a handful of other interns in the FLBS internship program even ended the summer by getting phytoplankton tattoos at Polson’s Black Diamond Tattoo Studio to commemorate their experiences. While Craft was unaware of the tattoo outing, he understands all too well the way Montana can leave a permanent impression on a person’s life.

“I can’t think of a better place to study freshwater ecology than Montana,” Craft said. “I’m a lifer.”